Good Startup Communication

What great teams get right

Brought to you by Wispr Flow: Effortless voice dictation. Write 4x faster in all your apps, on any device. Professionals at Perplexity, Substack, and Superhuman use Wispr Flow for over 70% of their communication — and so do I.

If you enjoy this essay, you’ll enjoy Wispr Flow. Get a free month of Pro here.

Product thinkers go deep within their space.

Deeper than their product shows. Deeper than 99.9% of others.

I did this at Superhuman: I obsessed over team communication.

Every startup faces these questions:

How should we communicate? Which tools should we use? When should we Slack versus email versus talk?

How responsive should we be? What response time is too slow or too fast? Is there even such a thing as too fast?

How should communication work for remote teams? Teammates constantly in meetings? OOO teammates?

These all resolve to one core question: What helps the team move the fastest?

You’d think these are solved problems. After all, every startup faces them.

Amazingly, no.

Reality: Startups stumble onward. Local optima emerge. Tension brews across teams.

Some startups claim intentionality. But they, too, land on suboptimal equilibria.

A classic example is startups mandating that 100% of communication goes through Slack. Sure, sounds good on paper.

But speak to any individual to see that they’re miserably drowning in an endless onslaught of comms.

A minority of startups think deeply about the problem. Shining examples include Stripe’s email transparency, and scaling email transparency, and Amazon’s Write Like An Amazonian.

But these cases are vanishingly rare.

Why is startup communication so hard?

Part of the problem is human inhibition. Fear of embarrassment, mostly.

Sometimes it’s a skill issue. A junior hire who hasn’t yet learned how to write succinctly. An executive who is chronically slow to respond.

And part of it is systematic: A simple absence of guidelines.

This essay documents foundational principles of good startup communication.

These principles should be of practical use to you.

You could personally start using them today. Or you could institute them for your entire team.

Principles of Good Communication

1. Effort Conservation Principle

Good communication conserves effort as much as possible.

Teammate attention is a finite resource. It is perhaps the team’s most precious resource.

Senders should be conscious of their own effort spent communicating, as well as the effort they demand of others who receive their communication.

Senders should seek to minimize both.

2. Efficient Expression Principle

Good communication is concise, but not at the expense of clarity.

The Efficient Expression Principle flows directly from the Effort Conservation Principle.

Verbose or unclear communication wastes teammate attention that could have been better spent elsewhere.

Concise and clear communication minimizes effort.

3. Appropriate Artifact Principle

Good communication uses appropriate artifacts to boost message salience.

Example artifacts might include:

A Notion page

A Loom voiceover

A spreadsheet

A quick diagram

The Appropriate Artifact Principle builds on the Efficient Expression Principle: Let the artifact do the talking so that you don’t have to.

A picture says a thousand words; a video says a thousand pictures.

4. Recipient Specificity Principle

Good communication explicitly addresses a set of recipients. Good communication is never vague on who is being addressed.

Recipient specificity ideally uses in-built tag functionality: “@” in most tools.

This principle requires that teammates understand each other’s roles and responsibilities well enough to know who to address.

This principle should be upheld for all communication types: Sharing information, posing a question, requesting work, and beyond.

And it should be upheld in all forums: Email, Slack, Notion, Drive, Figma, GitHub, Linear, and beyond.

5. Recipient Minimization Principle

Good communication does not just specify recipients, but actively minimizes the number of recipients required to consume information.

Good communication never requires an individual to consume information that they do not need.

The Recipient Minimization Principle flows directly from the Effort Conservation Principle combined with the Recipient Specificity Principle.

6. Information Access Principle

Good communication defaults to public channels for all valuable and non-sensitive information. It is bad communication to sequester such information in private silos.

Crucially, per the Recipient Specificity Principle and Recipient Minimization Principle, the Information Access Principle does not suggest that every teammate is forced to read every communication.

It merely requires that individuals are able to access information if they want.

A practical example of the Information Access Principle would be starting a growth-related conversation in the public #growth channel, rather than DMing the growth PM.

Of course, only the relevant individual(s) should be tagged in the channel.

There is a critical consequence of the Information Access Principle:

Most messages sent in public channels should be ignored by everybody who was not explicitly tagged.

For most, this comes as a huge relief: Freedom from drowning in an endless sea of comms.

The longer-term benefit of the Information Access Principle is that information can be easily discovered by others.

This safeguards against the reality that roles and responsibilities are ever-changing, such that information may be relevant for a different set of individuals tomorrow than today.

The Information Access Principle requires that individuals proactively shift conversations into public forums, rather than letting them proliferate in private.

What defines valuable and non-sensitive communication?

Valuable is anything that might further the company.

Sensitive requires private discussion because public discussion would distract the team or create undue risk. This might include personnel matters like feedback, hiring, or compensation. It might involve private information like API keys or PII. Or it might relate to delicate projects such as a fundraise or M&A.

Sensitive topics should be the minority of a typical teammate’s total communication. However, some roles like Recruiting or Corp Dev might have a higher share relative to other roles.

7. Independent Discovery Principle

Good communication recommends that individuals should not request information that can be easily looked up.

The Independent Discovery Principle is unlocked by the Information Access Principle.

Consider a fast-growing organization.

There will be an ever-growing body of knowledge. There will also be an ever-growing number of individuals who need said knowledge.

The team suffers if teammates disrupt each other every time information is needed that could have been independently discovered.

Therefore, individuals should seek to independently discover information they want, and only ask if it is not found after a quick look.

Finally, after receiving the answer, individuals should make high-salience information easier to find in the future. This might look like updating keywords on existing information to make it appear faster when searching.

8. Thorough Response Principle

Good communication responds to every point made in a prior communication.

Furthermore, good communication makes clear precisely which part of a message is being responded to, for maximum clarity.

This ideally uses in-built quote functionality, for example typing “>” in most rich-text editors, or a feature like Quick Quote in Superhuman:

The Thorough Response Principle upholds the Effort Conservation Principle: It is extremely burdensome for a sender to double-check that all of their points were handled. This principle relieves senders of that burden.

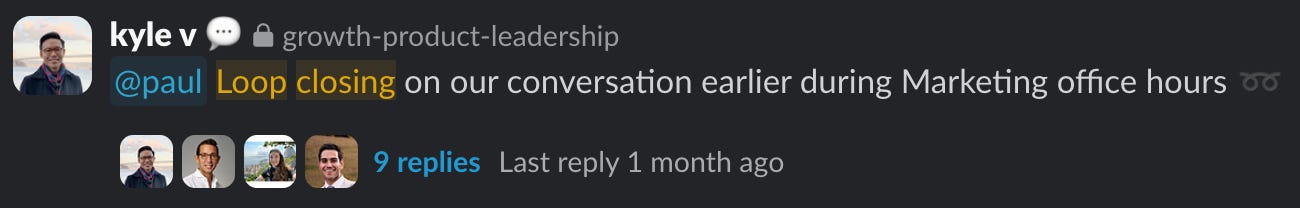

9. Closed Loop Principle

Good communication closes the loop on all open topics of discussion. Good communication never leaves threads hanging.

The Closed Loop Principle is a special case of the Thorough Response Principle, for tasks that naturally involve a delay.

Of course, it is not practical to chase down every idea to completion in the sense of actually completing the work.

Therefore it is reasonable and even encouraged to close loops with the simple message: “I’m deprioritizing this topic.”

10. Channel Norms Principle

Good communication depends on teams defining shared channel norms. Each teammate should understand those norms so they can communicate with intentionality.

Teammates should never feel like they are picking randomly when deciding which channel to use.

What is a channel? The concept can exist at several levels of abstraction.

For example, teams can communicate in different platforms like email or Slack.

Teams can also communicate in different spaces within platforms, such as different Slack Channels.

Channel norms should exist for all relevant levels of abstraction.

Channel norms should be clearly written down, for example in a company Wiki or handbook.

They should be considered required reading for all new teammates, and any meaningful updates should be pushed to the entire team.

The most important norm to agree on is a responsiveness level per channel. Responsiveness levels should be set to the fastest possible turnaround that is not disruptive to meaningful work.

It is better to respond faster than slower. If information traveling through an organization represents small increments of progress, then slow responses hold back that progress.

But at the same time, communication can slow down other forms of progress, notably individuals making strides forward in their own work.

Responding to every Slack within 1 second would be disastrous for meaningful individual work, despite being excellent at ensuring that collaboration never stalls.

Different channels also naturally tilt towards different responsiveness expectations. The form factor of Slack lends itself to semi-synchronous discussion, whereas the form factor of email promotes more reflective asynchronous exchange of ideas.

So what should responsiveness norms be?

A good starting point is that everybody responds to Slack within 3 working hours, and to email within 1 working day.

To uphold these, equip your team with appropriate tools like Wispr Flow and Superhuman.

11. Channel Nuance Principle

Good communication permits individuals and sub-teams to adopt more nuanced norms per channel, so long as they do not subvert the team’s wider channel norms.

Let’s say the team agrees that emails should be read and responded to within 1 working day. It is obviously good for the organization if some individuals and sub-teams choose to respond faster.

On the other hand: It would not be good if an individual or sub-team consistently responded slower.

In line with the Information Access Principle, individuals and sub-teams should transparently share any channel nuances they have adopted, to make it easier for others to communicate with them.

However, because nuances should never subvert the wider company’s norms, these should not be considered required reading for others.

Individuals should be able to freely communicate without needing to learn everyone’s peculiarities and preferences.

12. Acknowledgment Principle

Good communication has recipients send acknowledgment of receipt as fast as reasonably possible. Acknowledgments inform senders that communications have been seen.

Valid forms of an acknowledgment include a Slack emoji reaction, an iMessage Tapback, a blue double-checkmark in WhatsApp, or simply responding “ack”.

To minimize disruption, acknowledgment must take the recipient as little time as possible.

And yet, brevity must never be mistaken for rudeness.

Acknowledgment combats the inherent uncertainty in asynchronous communication that arises from a lack of non-verbal cues.

When senders cannot physically see a recipient’s subtle head nod or thumbs up, efficiently communicating “I saw this and it’s on my radar” goes a long way.

13. Notification Sovereignty Principle

Good communication requires each individual to take full responsibility for their notifications. Notifications include alerts, banners, badges, counts, sounds, email updates, and more.

The Notification Sovereignty Principle relieves senders of the need to consider the notification settings of their recipient. After all, that is the responsibility of the recipient.

In turn, senders do not need to feel responsible for the consequences of those notifications. This frees senders from the mental overhead of constantly having to consider the timing of their communication.

Senders can communicate whenever they want, which is usually as soon as they can. This prevents communication from being arbitrarily delayed for fear of disturbing the recipient.

In the extreme, the Notification Sovereignty Principle implies it is perfectly reasonable to send communications at 3 AM or the in middle of the weekend if desired. It should also be perfectly fine to tag a teammate who is Out Of Office.

Sender mental overhead and arbitrary message delay are significant taxes in organizations of all sizes.

The Notification Sovereignty Principle nearly fully eliminates these taxes.

14. Notification Suppression Principle

As a crucial counterpart to the Notification Sovereignty Principle, good communication encourages teammates to suppress notifications so that they are minimally disruptive.

Unfortunately, most communication tools have the exact opposite as their default: Red badges, stressful numbers, moving banners, noisy sounds, lock-screen widgets, and more.

Notification defaults are disastrous for focus.

Most teams, particularly those whose work depends on a maker schedule, unlock improved productivity when individuals minimize notification disruption.

How can a team uphold the Notification Suppression Principle yet also be responsive?

Individuals should proactively check communication channels. This should not happen in response to notifications. It should instead align with their team’s Channel Norms Principle.

For example, if the team has agreed that emails will be responded to within 1 working day, then each individual should proactively check their email at least once per working day.

All individuals should carve out at least one “in case of emergency” channel where notifications will reliably disrupt them. Usually, this is “walk over to my desk” or “call me”. Senders should use these channels sparingly.

Similar to the Channel Nuance Principle, some roles might elect into a higher degree of notification disruption. For example, an engineer would reasonably allow PagerDuty to always make a noise. A salesperson might reasonably want email banner notifications.

Individuals may communicate their specific notification settings to others. However, thanks to the Notification Sovereignty Principle, senders should not be required to understand this information before communicating.

15. Responsible Recipient Principle

Good communication requires that all recipients responsibly handle their inbound communications.

Specifically: They should catch up on all messages since the last time they were online. This should be upheld regardless of how long they were offline.

The Responsible Recipient Principle relieves senders of the need to chase down replies.

It further relieves senders from having to create systems to facilitate said chasing, such as setting reminders on outbound communications.

If upheld, this principle releases senders from a significant amount of mental overhead.

Adoption

Some of these principles are uncontroversial, like the Effort Conservation Principle or Efficient Expression Principle. Any reasonable person thinking about them for a moment would buy in and adapt behavior.

Many are a question of skill, like the Appropriate Artifact Principle or Responsible Recipient Principle. Luckily, teams have self-reinforcing mechanisms that strengthen the adoption of these principles. The more individuals uphold them, the more effective they become in their role, deepening their adoption while influencing those around them to do the same.

But some resemble a Prisoner’s Dilemma, like the Information Access Principle or Channel Norms Principle.

When everyone participates, everyone benefits. But as organizations scale, individuals might subvert these principles for personal gain, even if it hurts the team.

Consider the executive who hoards information to build political influence, subverting the Information Access Principle. Or the salesperson who constantly swings by desks to move their deal forward even if majorly disruptive to others, subverting the Channel Norms Principle.

Of course, if everyone adopts these habits, everyone suffers.

While there is no silver bullet for adoption, several factors go a long way:

Hire intentional individuals. Seek characteristics like “looks before leaps”, “capable of deeply engaging with ideas”, and “thinks from first principles”.

Train the team. Write down norms and expectations, and make them required reading for all existing and future teammates.

Foster a culture where everyone has permission, and indeed, feels an obligation to remind others of the principles. Individuals should focus on the mutual benefit of the principles versus dogmatic rule adoption.

Encourage reflection. Is the system breaking? Revisit and iterate.

Pick good tools and sensible defaults. For example, at Superhuman, we discourage using Google Docs due to its inherent low discoverability, and instead recommend Notion.

We furthermore encourage new teammates to carve out space for non-sensitive thoughts. This default helps teammates rarely make the mistake of failing to invite collaborators to their pages — upholding the Effort Conservation Principle and the Information Access Principle.

AI

It is clear that AI has the potential to help vast numbers of people uphold good communication principles.

Tools already help: Glean accelerates discovery; Superhuman boosts responsiveness; Wispr Flow unlocks speed; Grammarly sharpens writing.

But can tools go further?

What if AI noticed when you forgot to reply to every point, violating the Thorough Response Principle?

Or prompted you to exit Slack DMs and move to a channel, to uphold the Information Access Principle?

And why stop there? These principles don’t just apply to human-to-human communication. They are just as relevant for AI-to-human communication.

AI agents — especially those showing up in our workspaces like Devin, Lindy, and Risotto — should be programmed with good communication principles in mind.

They should instantly acknowledge messages, respond thoroughly to all points, be specific in who they are addressing, and more.

If anything, well-designed AI agents may end up teaching us: Exhibiting communication so principled that we improve through pattern recognition and imitation.

Thank you Matt Waters for draft input, and for your intellectual fortitude in helping me interrogate the most arcane minutiae of good communication principles.

great article